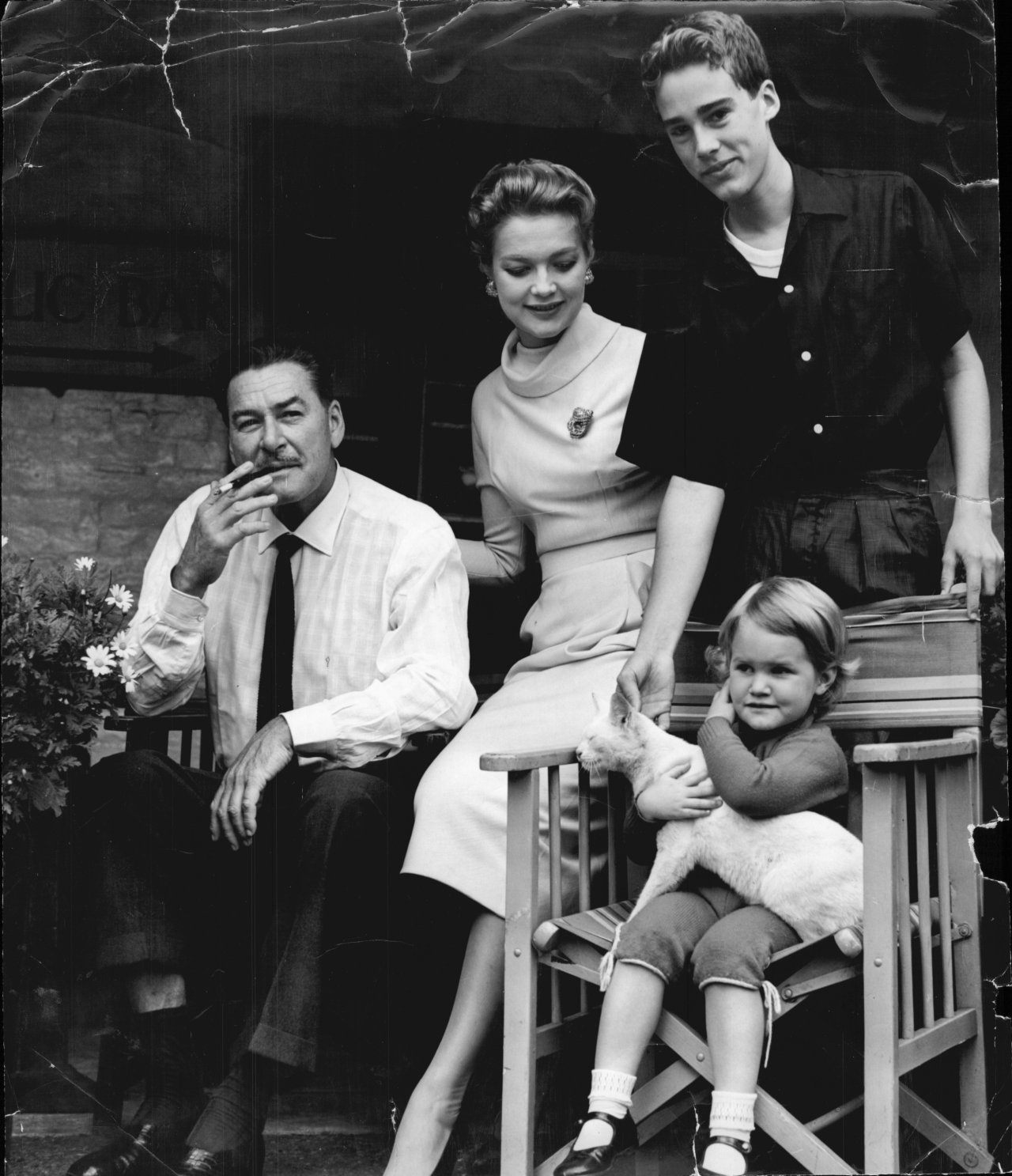

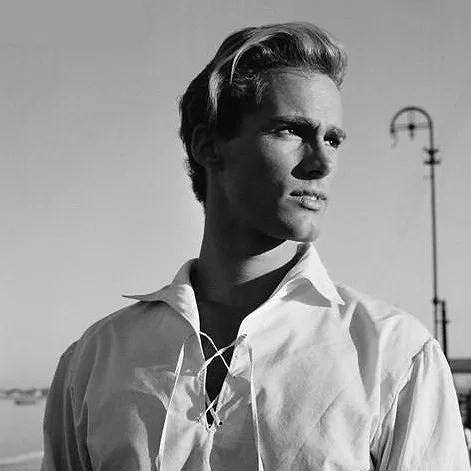

When 28-year old B-movie star and photojournalist Sean Flynn disappeared on April 6, 1970, his mother left his apartment untouched for over 20 years in hopes her son would someday return. Devastated by the loss of her only child, French actress Lili Damita never stopped searching for him until the day she died. Five years ago, I’d previously written about Sean’s similarly tragic stepsister Arnella on this blog, and now it’s time to examine the fascinating life of another doomed Flynn family member.

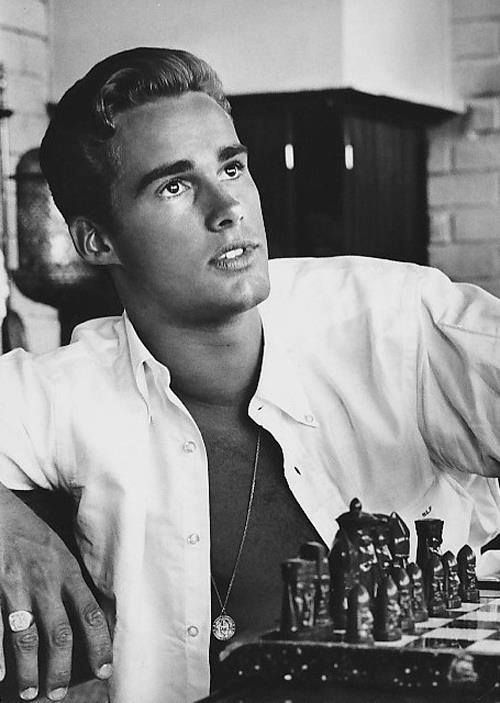

Sean was the son of Australian actor Errol Flynn, but unlike his father, he was less of a hellraiser and more soft-spoken and introverted, yet had an obsession with danger and thrill-seeking just the same. He sought to establish himself as the polar opposite of his father, but in doing so, he lost his life.

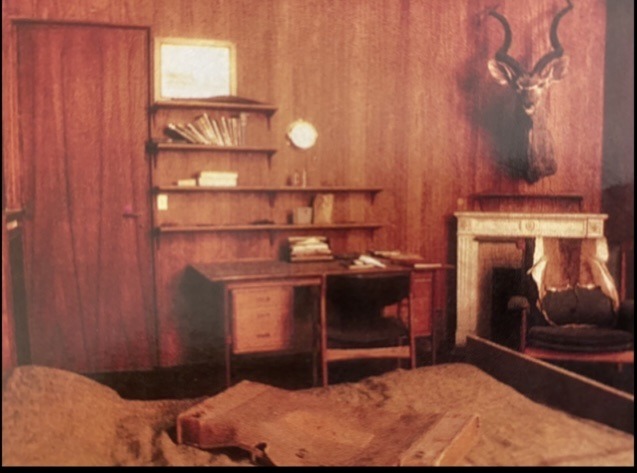

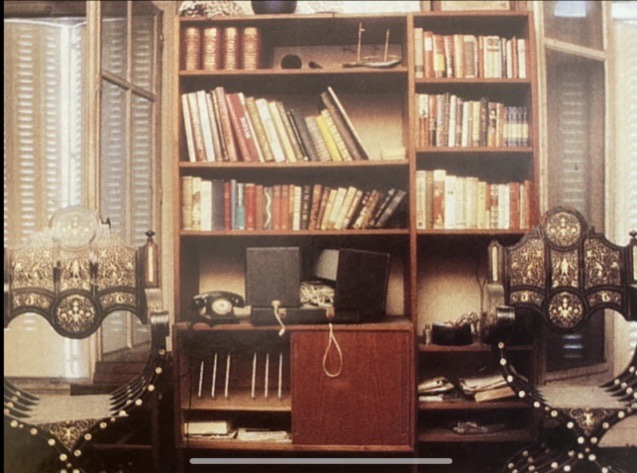

Sean’s Parisian apartment on the Champs Élysées was sealed by his mother to preserve his memory and remained a time capsule of the 60s until it was opened up after the death of Lili in 1994.

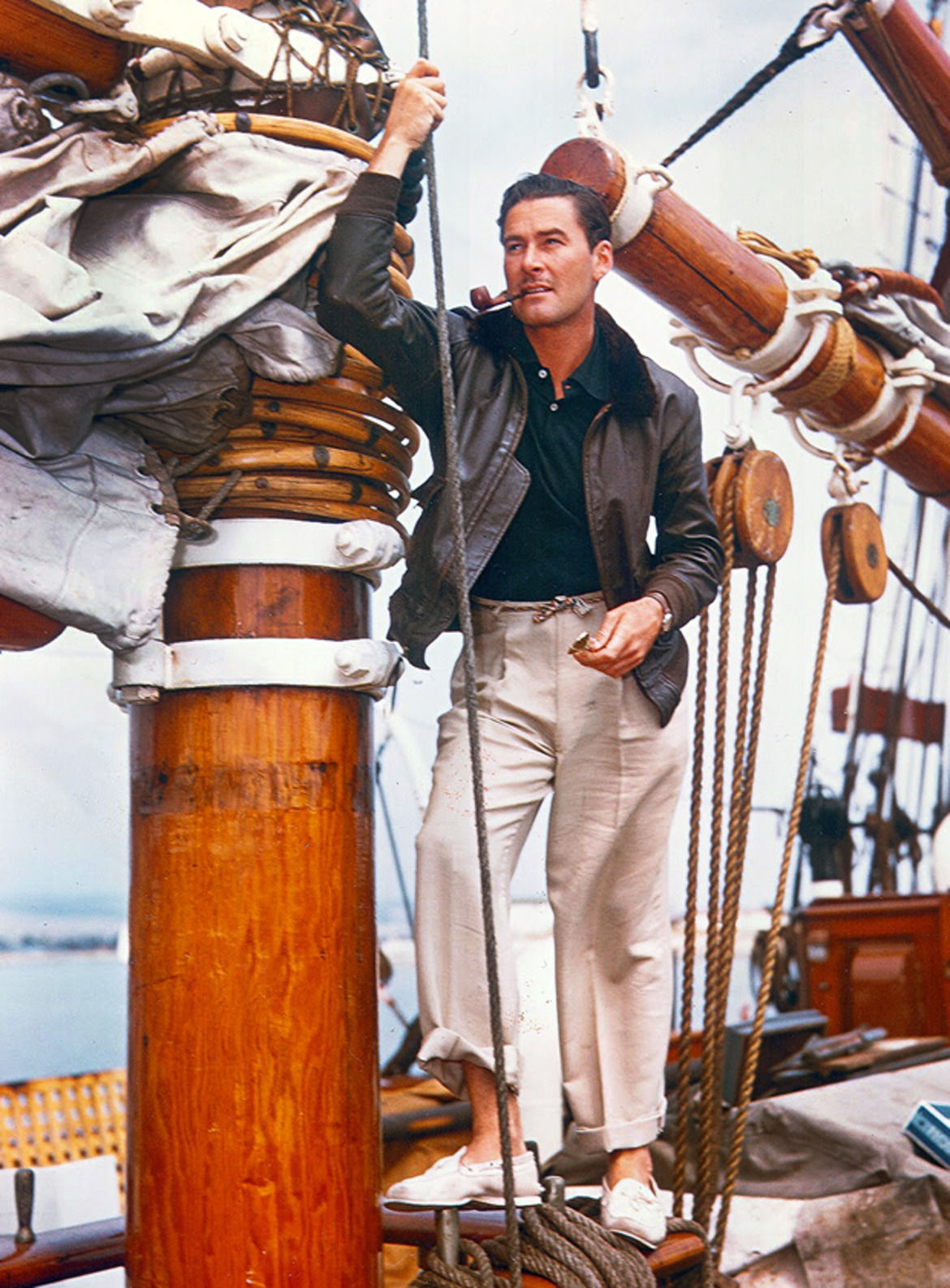

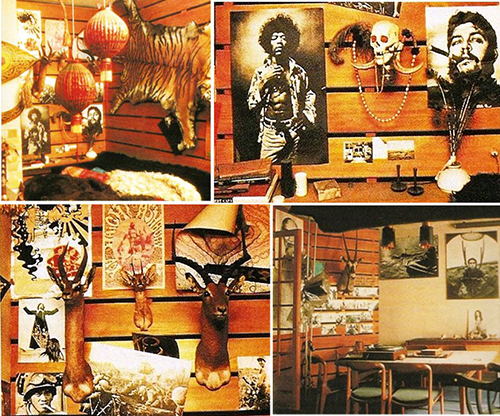

The walls were plastered with images of counterculture figures such as Jimi Hendrix, Che Guevara, and Ho Chi Minh, pictures of Sean travelling around the world as well as skydiving and hunting, copious amounts of taxidermy, a miniature of the Zaca (his father Errol Flynn’s yacht), expensive camera equipment, books, rolls of undeveloped film, psychedelic-patterned ties, unopened mail, and snappy clothing.

Sun Day magazine described the apartment as a “weird mixture of 60s flower power and very gruesome souvenirs” from his stint as a game hunter in Africa. It was if Sean Flynn and his larger-than-life personality were somehow speaking from beyond the grave.

After moving to Europe to start an acting career and recording a music album, Sean grew bored and went to Vietnam in 1966 to risk his life by becoming a combat photojournalist. Not the usual path for a Hollywood nepo baby, but Sean was no ordinary person. In a February 21, 1969 interview with journalist Zalin Grant, he gained access to Sean’s conflicted psyche:

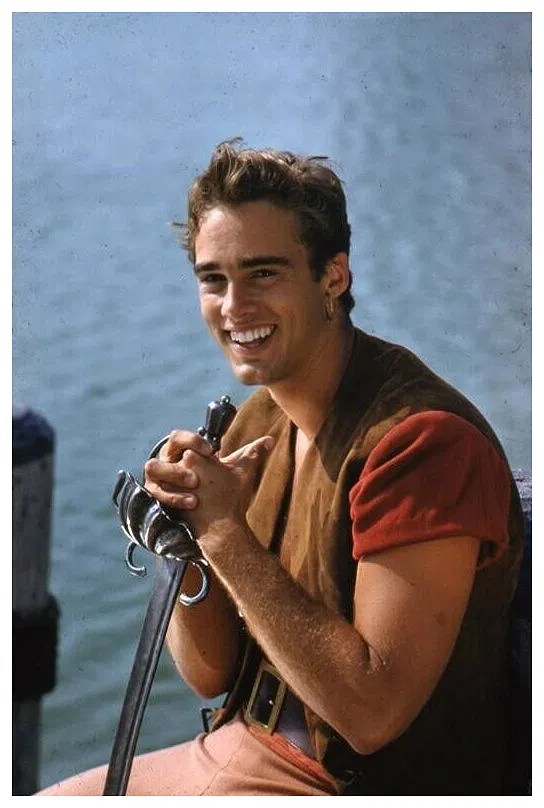

“When I was fifteen I got sent to a prep school in New Jersey. It depressed me. I didn’t like the Brooks Brothers atmosphere… I didn’t want to go to an Ivy League school. Get a business degree, work on Wall Street, marry a socially acceptable girl. It just wasn’t there. The summer I got out of prep school… the producer who’d done the original version of “Captain Blood,” the film that made my father famous in 1935, gave me a call and said, “Look, how would like to do a real film?

I’ve got this great idea—‘Son of Captain Blood.’ …So I dropped out and went to California, to get ready for the film. I did a little fencing with stunt men, took voice lessons. This went on for six months. I enjoyed the work but I soon wanted to get out of California. Perhaps I’m a conservative at heart, but I had to get out. Out of that smog and away from those freeways. Everybody I met was extremely cynical and knew everything. To them, screwing a girl had nothing to do with love. Even liking a girl was a kind of therapy. Life just didn’t have much meaning.

And I was trying to get away. My mother is a very generous person with her attention. I felt smothered, I guess, by her generosity. What can I say? I was a bit like a hick coming to the big city. I met quite a few young actors. The scene gyrated between Palm Springs and Hollywood to Malibu. I fooled around, but I wasn’t interested in it. I’m not the gregarious type. I don’t make friends easily. At nineteen, I felt very ill at ease and out of place.“

Feeling directionless and lost in the shallow world of Hollywood, Sean left his privileged lifestyle in a doomed quest for truth as a war journalist. Sitting in his French apartment, Sean decided to call up Paris-Match magazine and was soon hired after the staff realized he was the son of Errol:

“I’d bought a Leica in Spain but I hadn’t done any work as a photographer… They were interested in Sean Flynn, son of Errol Flynn, at war. I caught a taxi at the Saigon airport and gave the address I’d got from the Paris-Match guy. The driver takes a look at it and says, ‘You sure you want to go there?’ I said yes. So he takes me there. I’ve got a couple of suitcases, an attaché case, a camera, and a tennis racket. I get out the cab and turn around to see this gaping hole of a wrecked hotel. This was early 1966 and the Viet Cong had blown it up a few weeks earlier. The American press office in Saigon didn’t want to accredit me. They said the letter I had from Paris-Match wasn’t sufficient. I got a girl in France to send me some Paris-Match letterhead stationery, and I wrote my own letter, which was accepted.

I heard there was going to be a big operation in the Central Highlands called “Masher-White Wing.” I caught a flight to the press center the First Cavalry Division had set up in tents. I didn’t know fuck-all about what to do. Christ, we landed in one of the hottest actions of the war! South Vietnamese troops were coming up with armored personnel carriers on one side. The North Vietnamese were on the other side. We were in the middle. And they were shooting it out. All the photos I took were bad—underexposed. But I was glad to be in Vietnam. Maybe it was proving something, I don’t know. A lot gets lost in perspective, a lot of old personal battles. After you get the shit scared out of you a few times, it’s easy to look back and forget what was actually going on in your mind.

You see, the movies were obviously something I didn’t like. I won’t say I wasn’t interested. But I always felt—I don’t mind fighting my father. But I realized I was fighting him on his own turf. It came down to that. I was in a false situation. But I felt at home in Vietnam. I found out right away that I liked the—it’s hard to say you like war. But I liked the excitement. I felt my strength would be my ability to function under fire, in this case to perform as a photographer.“

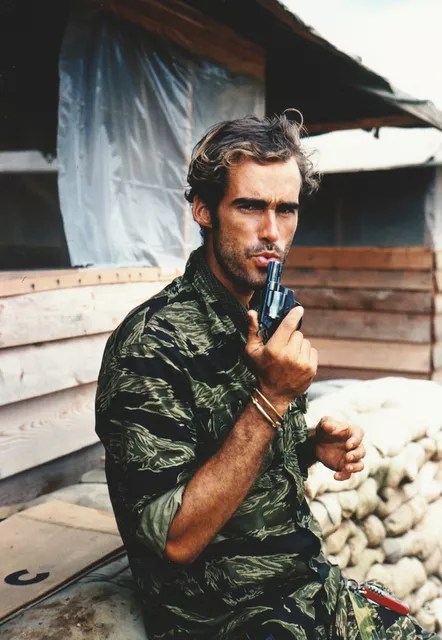

His images were published around the world and he helped save an Australian platoon from being blown up by a mine, as well as numerous other brave acts, though he never bragged about it or sought special attention. But a resentment began brewing in Sean when he realized that the war in Vietnam was unjustified and that the U.S. Army was responsible for the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians:

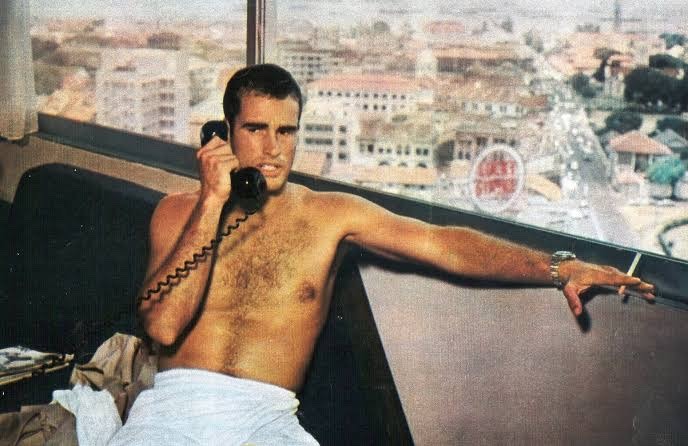

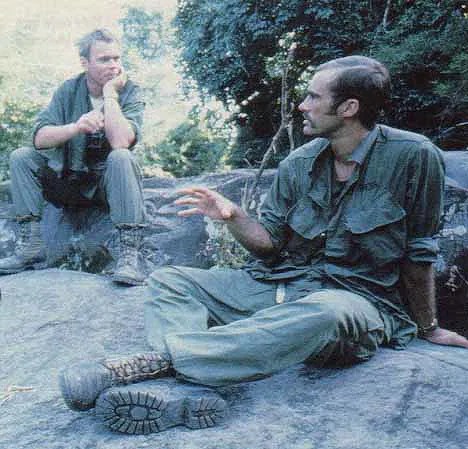

Photograph by Tim Page.

“It became clear to me that the war was a mistake. I went through several stages where I hated the whole thing. Anything American I was really ashamed of. As time went on, though, I realized that the soldiers in the field were some of the most interesting people I’d ever run into. I was in a position to meet a large cross-section of America, my contemporaries whom I’d never been able to communicate with before.“

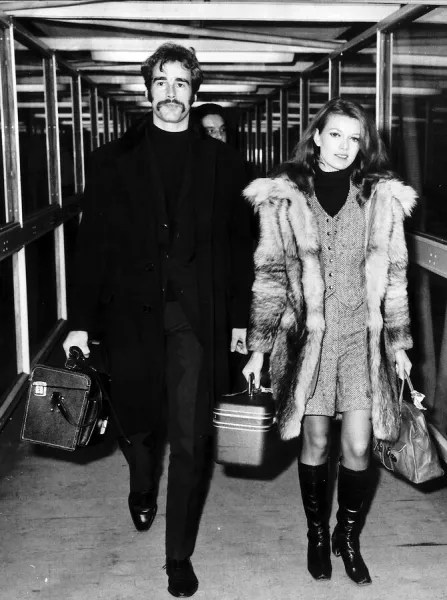

For his whole life, Sean was sheltered by a loving but overbearing mother and had immense financial and social privilege. Now, he risked his life daily by going out to photograph violent combat, which was slowly turning him into an adrenaline junkie. He hoped to one day make a documentary and write books on his time in Vietnam. In 1969, Sean took time off from photojournalism to travel around Southeast Asia, including Bali, Cambodia, and Laos:

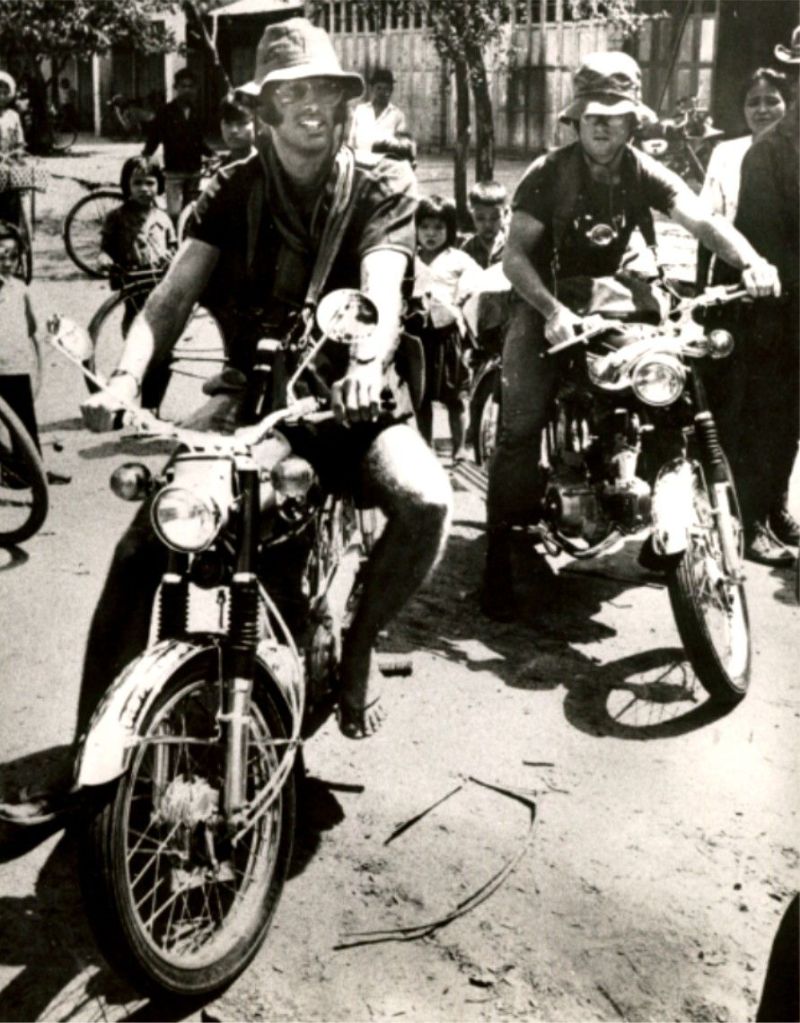

“ I’ve gotten on to this bike thing. I want to drive around Asia on a motorcycle. You are much more in contact with what’s going on. I want to go to Laos and buy a bike and drive around there, then Cambodia. I’ve gone through my crucible in the past six months. I don’t know what triggered it. Angkor Wat was very important. I got involved with the camera and a little bit of acid. I saw things in a completely different light. Drugs were a part of my education. But I can’t go along with taking them. You’ve got to go beyond that. I’ve decided that for the rest of my life I’m going to play the game my way. The game in the Buddhist sense—the Divine Joke of it all.”

Following his profound spiritual side quest, Sean decided to go back to war photography in 1970, after Cambodia faced a violent crisis under the Khmer Rouge. Sean’s bravery would cost him dearly when he and fellow journalist Dana Stone disappeared on April 6, 1970 after being kidnapped at a military checkpoint near Phnom Penh, Cambodia. They were most likely held captive for years, and then executed by the Rouge in 1973 near Kratie City, in the north by the Mekong River. Their bodies were never found, and it boggles the mind to think of the horrors the two witnessed before their grim deaths.

His heartbroken mother Lili Damita spent millions of dollars and the rest of her life desperately searching for her son, but it was of no use. Sean’s tragic fate remains a hazy mystery to this day, but his legacy lives on. Sean Flynn was many things: a B-movie star, nepo baby, crooner, a beach bum in Bali and California, prep school kid, game hunter, fencer, biker, avid traveler, college dropout, and war hero; but most of all, he was a valiant and daring photojournalist who gave his life for the ultimate scoop.

All of the quoted text in this article is from journalist Zalin Grant’s incredible feature “The Sean Flynn I Knew.” Without this interview, we would never have had such a deep insight into Sean’s fleeting but important life. I highly recommend his website to anyone interested in getting a first person perspective of the Vietnam War.